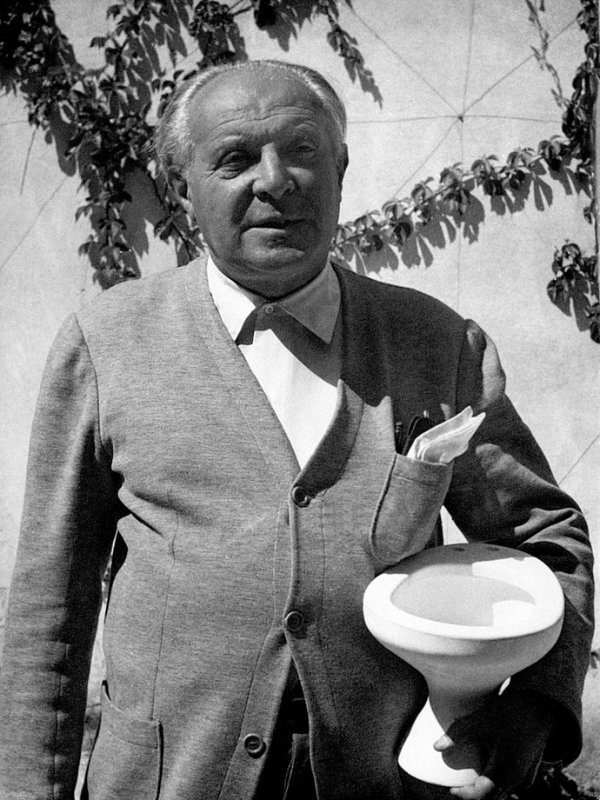

Few designers shaped twentieth-century Italian design as completely as Gio Ponti. Architect, industrial designer, furniture maker, and artistic director, Ponti blurred the line between architecture and object, between the monumental and the everyday. Whether architecture and interior design or editorial and philosophical, his work always carried a surprising sense of optimism one might imagine at odds with industrial design; he believed that modern life could be both functional and joyful.

Born in Milan in 1891, Ponti’s career spanned more than six decades. Ponti founded Domus magazine, designed buildings across Europe and Latin America, and collaborated with leading manufacturers like Cassina, Molteni&C, and Fontana Arte. His furniture, much like his architecture, expressed clarity without losing lightness; his designs stood apart for their unique ability to pair precision and play.

Ponti’s approach to material and proportion is still just as relevant today as it was in postwar Italy. The following seven pieces capture the international design icon’s inventiveness and artfulness.

All About Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti was born in Milan in 1891 and studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano after returning from World War I. He married Giulia Vimercati soon after graduating and quickly built a career that moved between architecture, interiors, and the decorative arts. His early work with Richard Ginori helped modernize Italian ceramics, and his collaborations with glassmakers, metalworkers, and furniture manufacturers expanded his reach.

He founded Domus design magazine in 1928 and used it to promote modern Italian design while teaching at the Politecnico for many years. Over six decades, Ponti designed more than a hundred buildings along with furniture, lighting, ceramics, and industrial products. His Superleggera chair for Cassina remains one of his most recognizable designs. By the time he passed away in 1979, he had become one of the central figures in twentieth-century Italian design.

Icons of Modern Design Crafted by Ponti

Ponti’s architectural work shows how naturally he combined structure, proportion, and surface. The Pirelli Tower in Milan is the clearest example: a slim, tapering skyscraper developed with engineer Pier Luigi Nervi that helped redefine the city’s skyline.

His residential work, including the Villa Planchart in Caracas, demonstrates how fully he imagined architecture, interiors, and furnishings as a single composition. Earlier projects in Milan, such as the Montecatini office building and the Branca Tower (Torre Branca), mark his transition from a classical vocabulary to a lighter, more modern one. These buildings explain why Ponti’s work still shapes conversations about modern Italian architecture.

Another of his most striking designs is the North Building of the Denver Art Museum, which is pictured above. Its faceted planes catch the light in different ways over the course of a day, and the narrow vertical windows give the structure a kind of lifted quality that still feels surprising. The materials are simple, mostly concrete and steel, yet the building avoids heaviness. Ponti was interested in how form and surface could shift as people walked around it, and that interest is easy to see here.

This combination of structure and imagination carried through to his later work and helps explain why these buildings still interest designers today. They were conceived thoughtfully and made to last, not only as objects but as ideas.

Seven Playful Gio Ponti Furniture Designs by the Italian Architect

Ponti’s designs are special because of how dynamic and timeless they feel, despite the fairly polarizing time during which they were issued. He often worked in wood and metal but treated both with the precision of an architect and the curiosity of an artist. Chairs were experiments in proportion; tables looked like sculpture.

His work, spanning decades and disciplines, feels united by a single idea: that good design should elevate daily life. He saw furniture and architecture as part of the same conversation, each shaping how people lived and moved.

D.153.1 Armchair by Gio Ponti

The D.153.1 Armchair is one of Ponti’s most recognizable pieces, and for good reason. Designed in 1953 for his apartment on Via Dezza in Milan, it reflects the period when he was rethinking how furniture could shape a room without overwhelming it. The brass structure draws a clear, almost architectural outline, and the upholstery (whether in the classic bicolor white-blue leather or the “Punteggiato” fabric he created in 1934) feels unique. That original fabric, which was a pattern of circles woven in velvet, shows how comfortable he was blending tradition with a more modern sensibility.

The chair’s profile feels distinctly midcentury, yet it never settles into a single era. The angles are sharp enough to catch the eye, but the proportions keep it welcoming. That balance explains why the D.153.1 moves so easily between different interiors. It feels light but steady and carries the kind of confidence that comes from a designer who understood materials and scale on an instinctive level. Molteni&C’s reissue stays faithful to Ponti’s original drawings, which is probably why it still feels so right today.

Superleggera Chair by Gio Ponti

The Superleggera might be the clearest expression of Ponti’s philosophy. Designed for Cassina in 1957, it weighs just over four pounds yet feels remarkably stable when in use. Ponti wanted to prove that strength could be achieved through precision rather than mass, and the resulting chair is both technical and poetic. The ash frame is so finely tapered that it almost disappears from certain angles.

What makes the Superleggera extraordinary is its continued relevance. Decades after its debut, it still feels fresh because it never relied on novelty. Ponti’s design distilled centuries of Italian woodworking into its purest expression: light, strong, and perfectly balanced. The chair has been exhibited in museums, used in family homes, and reissued countless times, yet it always looks so contemporary. Few designs achieve that balance of function and grace. The Superleggera is proof that precision and restraint can make a design endure past the life of its creator.

Coffee Table by Gio Ponti for Giordano Chiesa

The Coffee Table for Giordano Chiesa reveals Ponti’s sculptural side. The glass top seems to float above a delicately joined wood base, its structure open and architectural. Each angle changes how you read the table’s form, which makes it as engaging to look at as it is to use.

Despite its lightness, the piece has presence. The craftsmanship is unmistakable: every joint, every curve, every line feels intentional. It reminds us how effortlessly Ponti could move from grand architectural gestures to small domestic ones without losing his touch.

D.154.2 Armchair by Gio Ponti

The D.154.2 is Ponti’s take on the classic lounge chair, though “classic” feels too modest. Designed for Villa Planchart in Caracas in 1954, it captures the optimism and experimentation of the era. The curved shell seems to hover above its base, giving the chair an almost sculptural lightness. The proportions are generous, but the lines are crisp, showing Ponti’s talent for turning comfort into design language.

What’s clever about this chair is how adaptable it feels. Its form nods to midcentury design, but the smooth upholstery and compact silhouette make it work in contemporary spaces too. Ponti was always interested in how people actually lived, not just how furniture looked. The D.154.2 proves that comfort and modernity don’t have to compete. They can share the same frame.

Settee by Gio Ponti for Cassina

The Settee for Cassina captures Ponti’s ability to make everyday forms feel light and precise. Designed in the 1950s, it’s compact but visually strong, with a tight back and angled legs that keep the profile clean. The upholstery often introduces subtle pattern or color, something Ponti used to soften geometry without losing structure. It’s practical, yes, but also elegant in the quietest way.

Furniture like this shows why Ponti’s influence reached beyond architecture. He understood scale — how a piece of furniture could define a space without overwhelming it. The Cassina settee feels refined yet adaptable, equally at home in a formal parlor or a small modern apartment. It’s a reminder that good design doesn’t demand attention. It earns it.

D.655 Dresser by Gio Ponti for Singer & Sons

Ponti’s dresser for Singer & Sons bridges craft and utility. Possibly from the D.655 series, the piece is all about proportion. You can view a painted D.655.1 dresser below; its legs are a bit more dramatic than those on the stained dresser pictured above. Either way, the drawers sit within a frame that’s both sturdy and refined, while the subtle contrast between walnut and brass gives it depth. Ponti had a way of making storage feel almost ceremonial, turning a functional object into something architectural.

The sculptural legs and clean lines remind you that this was midcentury design at its best: warm, useful, and beautifully made. Nothing about the dresser feels showy, yet everything feels considered. Even today, it would fit easily in a contemporary home. Ponti’s genius was in designing for the long view; his pieces are meant to last in both structure and style.

Drop Leaf Apta Table by Gio Ponti

Last but not least, the Apta Table sits firmly in Ponti’s late career, when he was experimenting with color, surface, and lightweight modern materials. Designed around 1970, it offers a clever mix of geometry and movement. The circular top swivels so the two leaves can fold down smoothly, shifting the table from a full round to a compact half-moon with almost no effort. The painted panels, which are often arranged in sharp, pie-slice segments of red, orange, or similar tones, give it a lively, graphic quality that feels unmistakably tied to this period of his work.

What makes the Apta so striking is the dialogue between the vivid top and the sculpted base. The three-part support feels architectural, almost like a small pavilion holding up a bright canopy. When the leaves are lowered, the shape completely changes and the color fields compress into a bold stripe. It’s practical, yes, but also a bit theatrical. The whole piece reflects Ponti’s interest in furniture that could shift, adapt, and still retain a strong visual identity, which is something he explored often in the 1960s and 70s.

Why Gio Ponti’s Work Still Resonates

Ponti understood the link between design and emotion. His furniture doesn’t rely on ornament or novelty but on clarity and proportion. Even his most playful pieces feel deliberate; they are built by discipline rather than on a whim.

This explains why his career impact has far exceeded Ponti’s own life. These works continue to speak to us because they capture a balance between intellect and instinct, between making and living. In the end, Ponti’s genius was not in invention alone, but in how he made modernism human.